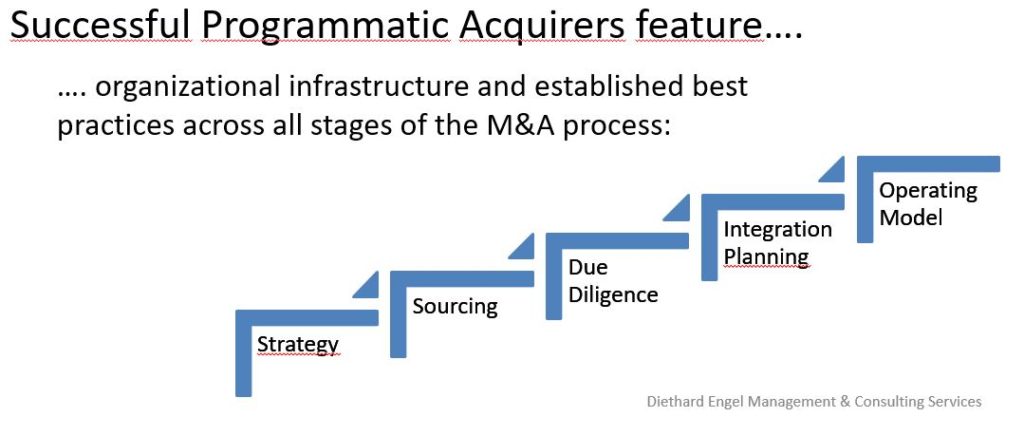

Everybody has heard horror stories of terrible M&A failures, destroying value and potentially bringing down entire businesses. On the other hand, many Corporations make M&A a continued success. They share a common recipe.

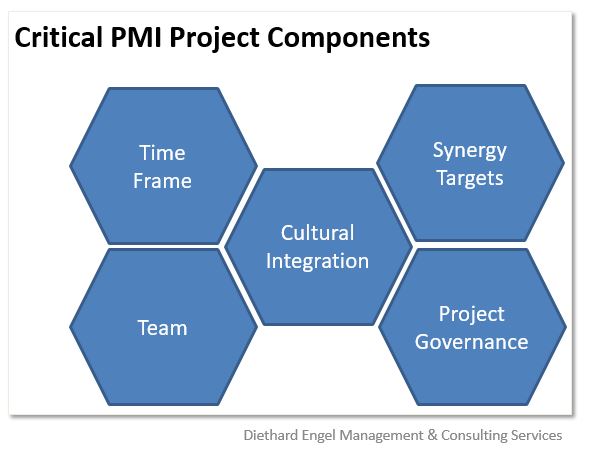

Luckily, we don’t have to invent the wheel over and over again: There is plenty of evidence from scientific analysis, market surveys and case studies that it’s a handful of components which decide whether or not a project setup will lead to post-merger integration success. Generally, successful acquirers sport

- A strong team;

- Strict project governance;

- Well-defined synergy targets;

- An ambitious timeline for completion;

- A people-centric approach to cultural integration.

Getting all of these right will not guarantee integration success, but certainly increase the odds for successful completion of a post-merger integration process.

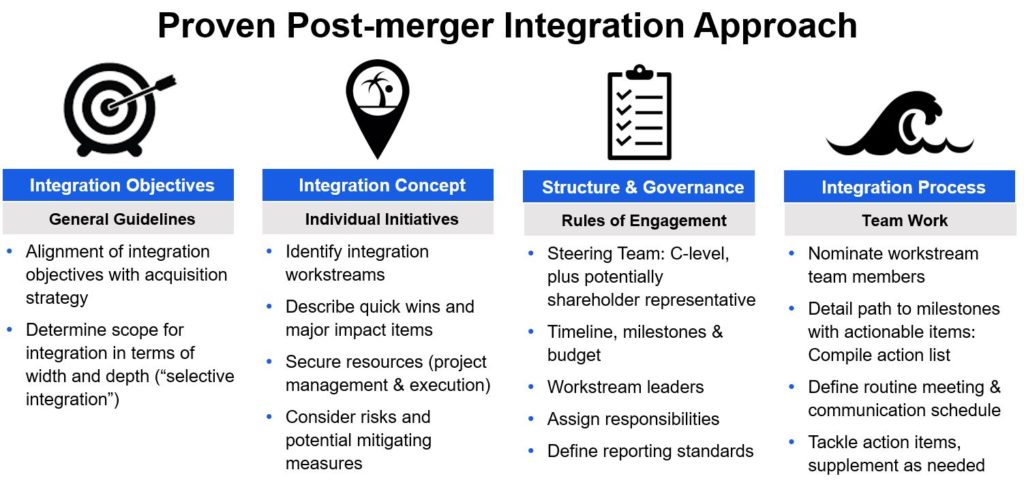

Admittedly, it is all but easy to get an integration right, however, there seems to be a proven path which we will explore in this and the next articles in my column “Inside Post-merger Integration”. Let’s take a look at the first key building block, the integration team.

An acquisition and its integration is likely to impact the entire organization, its structure, processes and behavior. That’s why I rather like to refer to PMI projects as transformation programs. (Linguistically, “program” seems to carry a little more weight than “project”.) Running a transformation program means serious business – you will want to get it right under all circumstances. It all starts with selecting the right people to help you with it.

Rule #4: Resource your program with top people

As one of my colleagues said once: Availability is not a skill set. Your integration team should consist of hand-picked, strong leaders, coming from both sides of the deal, buyer and acquiree. A dedicated team lead, a skilled PMI Manager, can be resourced from the outside (consider an interim manager with methodical and implementation know-how), but the rest of the team should be from within the organizations, if at all possible.

Integration activities will take up time – a lot of time, while business continues. This may put an undue strain on the resources, and should be considered already in the setup. Adding functional backup to deal with day-to-day business while the department head is distracted with project work is a proven response.

The integration team structure will reflect the strategic business intent: The target operating model dictates the functional (and/or regional) areas of integration (compare the previous article, “Pre-deal Planning”) – and the integration team aligns with the areas of integration. Usually, the team is organized by workstreams, with each workstream representing one integration area. Each integration workstream should be led by the relevant functional manager. Ideally, there is a good balance between the buyer and target in leading and staffing the workstreams, for example representative of size.

Diethard Engel is an independent consultant and interim manager, focused on Business Transformation, Post-merger Integration / Carve-out and Executive Finance in the manufacturing industry. He has run multiple post-merger integration/carve-out projects for international businesses.